Today’s post is by my very good friend, Brett Land. Brett is a professor of philosophy and religious studies and uses words better than any other person I have ever met. Today I am so honored to share his reflections on the music of Justin Vernon (Bon Iver) and how it can help us think about transcendence and religion in ways that rupture our expectations and our traditions. In so doing, Brett shows us how Vernon might also invite us deeper into the significance of existence and the immanence of the divine.

Justin Vernon (Bon Iver) and “the This”

written by Brett Land

If I told you that Justin Vernon's music has profoundly shaped my life—enriched it, even—you might be inclined to dismiss this as bluster, so here's a couple of facts: when my wife and I selected the music that would accompany her as she walked down the aisle, we didn't choose Mendelssohn's "The Wedding March," or Wagner's “Bridal Chorus,” but Bon Iver's "Beth, Rest," a keyboard driven power-ballad with synthesizers and obtuse lyrics that makes me either want to weep or run five miles.

The album version of the song is soaring, epic, but the pared-down version, with just piano and Vernon’s baritone making way to a falsetto, will bring you to tears. If you have not heard "Beth, Rest," this version approximates what it sounded like--on harp, played by our talented friend Anahita--at our wedding.

The song didn't so much match the moment as lift it into an entirely different territory (which is about all you can ask of a song that is marking one of the most important moments in your life).

***By the way, I’ll use “Justin Vernon”—the historical person from Eau Claire, Wisconsin, that attended the University of Wisconsin at Eau Claire and majored in Religious Studies and Women’s Studies—and “Bon Iver”—the outfit assembled by Vernon that is part band, part art-project, part vibe—more or less interchangeably in what follows.***

Here’s another fact: one summer, circa 2008, when I was trying to summon the courage to end a relationship, and the following summer, circa 2009, when I was grieving the death of that relationship, I listened to “Re:Stacks”—a languorous, paired-down acoustic guitar song that has Vernon singing in the highest range of his falsetto for the entire length of the song—so many times in a row that it seemed to have seeped into my nervous system. I concluded it was one of the most haunting evocations of melancholy and beauty ever recorded. Full stop. I am aware that Vernon’s company here is the very apex of American music: John Coltraine, Miles Davis, James Brown. “This my excavation,” Vernon opens the song, “and today is Qumran.” Listen for yourself:

I could go on with stories about his songs. I have one about "Calgary." I have a funny one about "Blood Bank."

I guess I’ve been obsessed with Vernon's music since 2007, when he released For Emma, Forever Ago, an album of acoustic songs that seemed to be written as if no one would ever hear them. In the three albums that Vernon has released since—and in the myriad number of collaborations he’s been a part of—he has consistently pushed into new sonic territory. The new albums are more ornamental, for one, with more synthesizer and drum tracks; in general, they have more stuff in them—all of which culminates with this year’s Sable/Fable, an album that has re-ignited my obsession with Vernon’s music (not that it ever really went anywhere). Sable/Fable marks a return to simplicity (the three songs of “Sable” are stripped-down to only Vernon’s voice and a guitar; and they have a frank, pseudo-confessional tone) as well as a call to embrace life (the songs on “Fable,” in contrast, are celebratory and drum-beat thumping and they make you want to get up and move).

I can think of few contemporary artists with the talent of Vernon, and certainly no other singer whose voice can stir together strength with the ethereal, haunting effect that his voice has. Don't believe me? Here's some proof of that, from his newest release Sable/Fable (note to children of the nineties that were paying attention to television at the time: Vernon takes the title of his band from an episode of the legendary television show Northern Exposure where the characters meet at the first snowfall of the year and great each other, in the French, with “bon iver,” a "good winter"):

I’ve been thinking about what it is that is unique about Vernon’s music, and why it works the way it does, and I want to consider a few things in relation to those questions about Vernon’s relationship to religion. More specifically, I want to sketch out a few lines of inquiry into what I see as Vernon’s concern with the transcendent, yet one that is embodied, imminent, and relational.

When I say that Vernon’s music evokes the transcendent—or brings it close—I don’t think we should necessarily look to his lyrics as proof of this. Vernon’s lyrics are often opaque, abstract, even inscrutable—I still don’t know what “Beth, Rest” is about, or “Calgary: (if by “about” one means a literal statement of feeling or affect). Sometimes a song will offer only a line or two of personal statement or direct-claim about something. Yet, Vernon’s lyrics are still frequently poetic, and they often give enough specificity that you can latch on to some aspect of what he’s singing. One also gets the sense that Vernon likes wordplay, as in the chorus of “There’s a Rhythm” when someone sings, “Day Fighter, Day Fire,” and then, “Stay minding, and mind it.” Sounds a bit clunky typed-out, but listen to it here.

When I talk about Vernon’s music and the transcendent, then, I don’t mean to suggest that his music is religious in any normative or traditional sense of the term—though the question of Vernon’s relationship with religion is rather interesting, and might offer some clues about why he is so frequently writing about religious themes. One might note the following: that he attended a Lutheran church with his mother from early in life until the age of thirteen, when they abruptly stopped going; that he studied religion in college, and that his senior thesis was titled, “Leaving Religion, Finding God;” and that references to religion, faith, and God are unignorable in his music; and that these references suggest an artist that doesn’t want to abandon belief entirely, as in “Ring Out,” a track from a pre-Bon Iver solo album that opens: “To the sermon on the mount, I am listening.” And the chorus of that same song: “J.C’s up for another bout, and I am ringing him out.”

You could do this for a lot of songs in the oeuvre, but “Heavenly Father” and “Faith” stand out as the most obvious places. In fact this acapella version of “Heavenly Father” is just haunting:

If Vernon’s lyrics aren’t to be taken as normative statements about belief but instead more of an exploratory wordplay and/or deconstruction of our expectations--and if, likewise, in interviews and podcasts, Vernon has explicitly distanced himself from traditional religion ("I'm no theist," he’s said recently), then what is it that seems uniquely religious about his music? What is it about Vernon’s music that feels, as Bob Dylan has said of Leonard Cohen, as if it were the "music of the higher spheres?"

Before we can answer that question—or even try—we might do well to consider what it is that we want from music in general? Do we want entertainment, distraction? Do we want music to evoke emotions or feelings? Do we want truth from music? Or knowledge? Or direction? Or meaning? Do we look to music to make us happier, or better, in some way?

Maybe.

The best music can probably do all of those things. But at the deepest level, the greatest music performs a magic trick whereby it transports us back to ourselves, back to the present moment, to the ineffability of the now, to the specificity of what I would call the This.

In an interview on Krista Tippett’s podcast On Being, the poet Marie Howe discusses the sui generis quality of poetry, or rather what it is that poetry does that is different from prose and other forms of writing. What is irreducibly unique about poetry? What does poetry capture that only it can? And why is that so?

In her attempts to think about this question, Howe suggests that poetry conjures the unsayable in language--that it makes a container for what cannot be said, but in such a way that it feels "inevitable." Howe emphasizes that poetry is prayerful, incantatory, and that there is a haunted silence between the lines of any given poem. She says that some poems have the quality of conjuring a “spell,” of “making magic with words” (to understand the incantatory aspect of poetry, think of a mother singing a child a lullaby—“this is maybe the first poem,” Howe says).

Then she describes an exercise that she gives her creative writing students at Sarah Lawrence College. She tells them to write "ten observations of the world." "Just tell me what you saw this morning," she says.

She continues:

“Well, it’s very hard for them to do. [I say] just tell me what you saw this morning. Like in two lines. You know, I saw a water glass on a brown tablecloth and the light came through it in three places. No metaphor. And to resist metaphor is very difficult because you have to actually endure the thing itself. Which hurts us for some reason. We want to look away—then the students say, well, there's nothing important to write about, which is of course the whole point of the exercise.”

At first, her students struggle, and want to embellish, adorn, and dress up their descriptions. But after a few weeks, Howe says her students start to bring in descriptions absent of metaphor or comparison or simile or abstract language of any sort; the bent flower stalk in the vase; the crumbs on the counter…She says that, by the end the term, her students understand that the thing they are describing is already something profound and it doesn’t need anything to make it more so.

What has happened here? What is this magic trick of writing? The students have begun to see the thing they are describing—the book on the table, the phone-charger caked in coffee dust—as irreducible, as comparable to no other thing, as sui generis.

We might call the thing they are describing the This, which is merely the present moment that is always already being rushed over, or ignored, looked away from, in endlessly creative manners.

Her students start to see the This.

Justin Vernon sees it too.

Later in that same interview, Howe mentions that someone had been going around Manhattan and putting up large signs, or placards, with large arrows and the words Happiness This Way—like a road-sign for Happiness Street, all around town. Over a period of weeks Howe would see these around town and eventually she starts thinking about how perfect they are, as these little moments of poetry, as reminders of the power of words, until one day she saw a group of people crowded around a big circle painted on the sidewalk. Everyone was smiling and pointing, some were taking pictures. On the sidewalk, an arrow pointed to the circle; the word, Happiness.

People were taking turns standing in Happiness, and all were smiling, even the ones that were standing to the side of Happiness, not directly in its orbit.

Another way to think about the transcendent is to recall Nicolas of Cusa's notion of the "coincidence of opposites."

Cusa thought this idea applied specifically to the notion of God's transcendence and imminence--that God could be both far and near, both many and one, both ordinary and special. The lion resting next to the lamb. The acoustic guitar and the synthesizer. The baritone and the falsetto. Leaving Religion, Finding God.

“Ever since I heard the howling wind,” Vernon sings on “Heavenly Father,” I didn’t need to go where a Bible went.”

“We have to know that faith declines,” he sings on “Faith,” “but I’m not all out of mine.”

“If there is a God,” his dad told him, moving his arms back and forth, in the air between the two of them, “it’s this.”

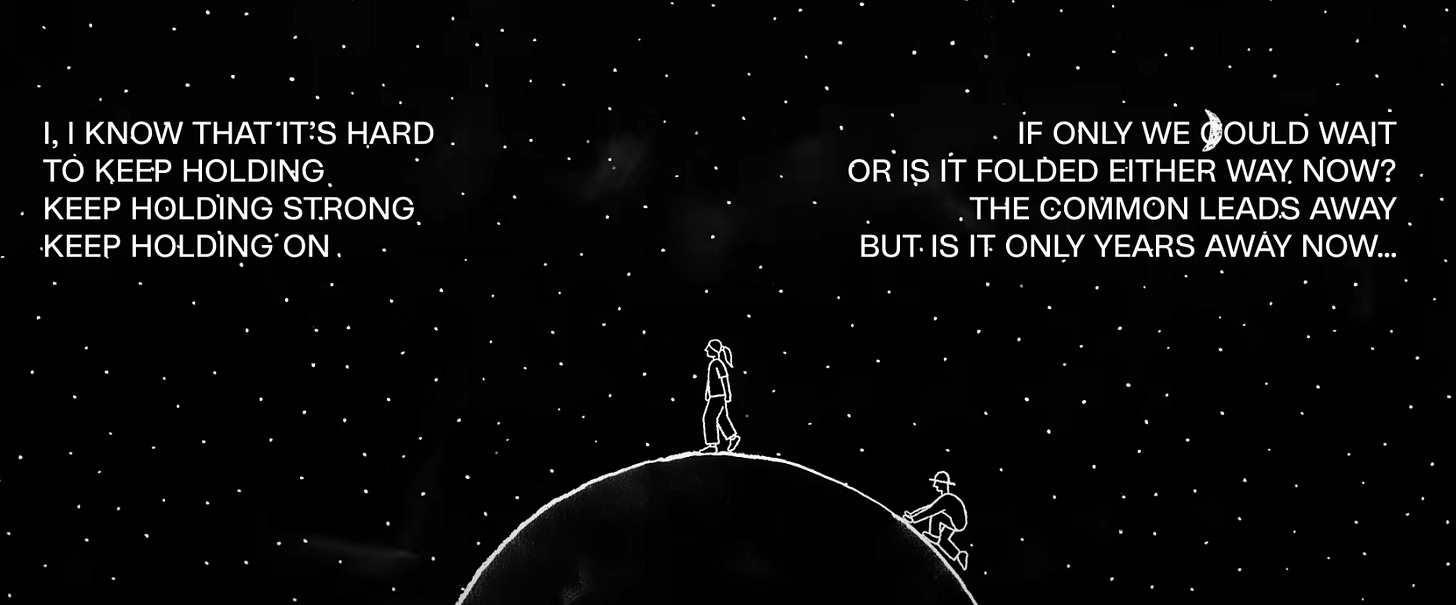

I was playing “If Only I Could Wait,” one of the new tracks from Sable/Fable, the other night when Clementine, my six year old, came into the room and started bobbing her head and bouncing to the beat of the song. She was in her peach-colored rainbow patterned pajamas and her hair was sopping wet. She’d originally come in the kitchen looking for dessert but had now forgotten about it because of the song. Who is this? She asked.

“Bon Iver,” I said, knowing she’d have no idea what it meant because they aren’t English words and because she is six.

What?

She was still bouncing with the beat.

Bon Iver, I said again but added: It's French. It means Good Winter. It’s from an old television show.

She was even more confused now, but still entranced by what the song was doing. She nodded her head. It is good, she said, but it isn’t cold.

Then she left the room, and I knew exactly what she meant.

I should have told her: Clementine: If there is a God, it’s this.

***Again, I want to thank Brett Land for this amazing reflection. I know what I will be listening too all day today while I struggle to get my own paper written! I hope it also becomes the soundtrack to whatever you think is worthy of your finitude today. Don’t forget to pay attention to the This. As the philosopher, Nick Riggle would say, “This beauty.” Or as Brett reminds us, This moment. This day. This song. This note. This dancing six-year-old. It all matters.

The first time I heard Bon Iver I felt a transcendence.