Greetings from Knoxville, TN. I am currently sitting in a hotel room having gotten here early so that I could go mountain biking on the local trails. Tomorrow (well today when you read this) I will be speaking at the University of Tennessee about how to phenomenology might help us have hope in the face of so many reasons to despair (oh, and there will be a lot about trout fishing in the talk too!)

Here is one of my slides from the talk - My dad, me, and my son all with nice trout!

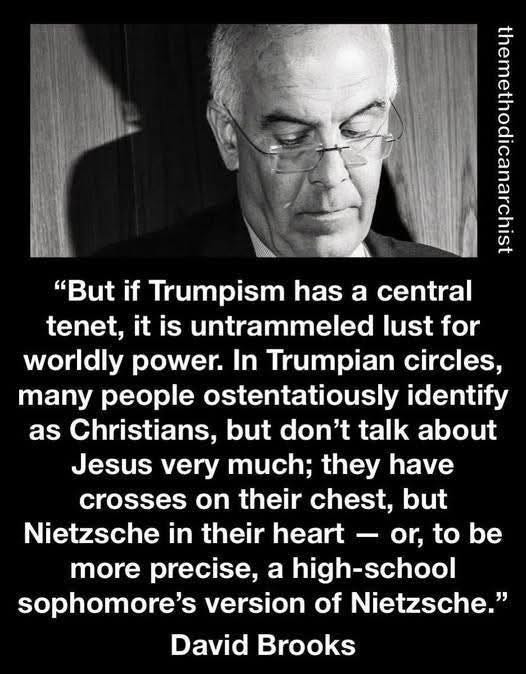

Anyway, I got back to my hotel with an idea of what I was planning to write about for this post, but then I checked Facebook before beginning to write (as one does!) and saw this:

I made reference to Brooks a few weeks ago when I discussed the idea that it is hard to know how to remain committed to reason-giving as a social good when so very many, especially those aligned with Trump, tend to care only about power and so no longer care about reason except to the extent that it might maximize their social power.

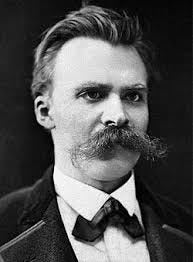

Well, I have seen several friends of mine post this quote from Brooks’s essay about the latent Nietzschean commitments of Trumpism and I have commented with affirmation on such posts, but then stressed that a lot of work is being done with the phrase “a high-school sophomore’s version.” That is to say, Nietzsche would be deeply opposed to Trumpist conceptions of power and rather than standing as a philosophical resource for Trump’s worst inclinations, he offers a profound critique of such social narcissism.

One of my friends asked me to explain how that could be possible given how easy it seems to understand Nietzsche as a predecessor of Trumpist idea of sheer-power-as-the-only-good. So, today I will at least try to lay out the basic shape of such an argument. It will lack substantive textual support (and yes, I know all my students will grade me very poorly for this since I do the same when they fail to provide textual evidence in their own papers!), but, again, I am sitting in a hotel room with an episode of the original MacGyver on the in background, so all you can do is the best you can with what you have where you are. ha!

When Brooks mentions a “high-school sophomore’s reading of Nietzsche,” I take him to be hitting on the same point that I try to make when I often say that existentialism is not just for goth-kids. To put a finer point on it, Nietzsche is dangerous when read by folks who listen to The Cure far too much.

But why is Nietzsche (mis)read by folks who often lack the training or background to be able to read his authorship responsibly?

Well, I think that there are a few reasons.

First, Nietzsche experiments with language in performative ways that often make it very difficult to track his arguments. Indeed, given his later aphoristic style, there often just isn’t much in the way of argument to be found in some of his most popular books. In this way, we might describe Nietzsche as the first philosopher of the modern era when attention spans have shortened and soundbites are more important than nuance. It is this aspect of Nietzsche’s writing that leads C.S. Lewis to say somewhere that “Nietzsche is a better poet than a philosopher.” As someone who prizes clarity and lucidity in my writing (to the best of my ability), and who thinks that philosophy fundamentally requires argument as the means of meeting its disciplinary obligations, I am actually sympathetic with Lewis’s assessment at some level. However, just because Nietzsche doesn’t often give the full argument to support his claims (i.e., he doesn’t show his work, as it were), that doesn’t mean that there are not arguments that can be supplied in the effort to be maximally charitable to the claims that he does, perhaps all too baldly, make. Accordingly, reading Nietzsche requires not only carefully attempting to reconstruct possible arguments that connect the dots of his aphorisms, but also it requires quite a bit of patience because even when Nietzsche says something very briefly, it if often the case that he is saying more with those few words than it might seem—hence why declaring him a poet might be more of a complement than it would otherwise seem.

Second, Nietzsche writes from a place of frustrated (and often deeply painful) isolation. He suffered from physical ailments for most of his life and during his especially productive period, he would take refuge in an inn high in the mountains far removed from the speed of cities and the crowds to be found therein. Why this matters is because Nietzsche often gives in to polemical expression that might have been tempered had he had to navigate things like neighbors, friends, colleagues, and tenure review committees. Free from the social constraints and humbling effect of social critique and audience engagement, Nietzsche ends up often saying things without the nuance and qualifications that might have been demanded had he been surrounded by people holding his feet to the dialogical fire. But, far from such challenge, Nietzsche was often given to rhetorical polemics that feel more like he was screaming at the void, than offering reasons for people to adjust their behavior. This leads Nietzsche to describe himself as “dynamite,” and claims that he is philosophizing with a hammer. One would surely be forgiven, especially if you are a sophomore in high-school, for concluding that Nietzsche was more about breaking things than he was about envisioning new ways of building a world.

Third, perhaps the most troubling and complicated aspect of his thought and, I believe, what is the most directly responsible for the misreadings of his work: Nietzsche almost idolizes the idea of power, the will to power, the very sense of power. He is unflinching in his critique of pity, of mercy, of weakness - which he sees as “Christian” virtues that actually undermine our very humanity. Moreover, his claim that “God is dead," his call for the “Overman” to emerge as the person who “transvalues all values,” and his encouragement that we move “beyond good and evil,” are all claims with which one must be very careful. Reading Nietzsche is kind of like trying to pick up a snake: There are safer ways to do it, but none are absolutely without risk.

Well, given his mode of writing, the polemical rhetoric that he uses, and the bombastic immoralist ideas that he proposes, I do not think that the high-school sophomore is all that blameworthy for thinking that Nietzsche is an anti-hero who calls us all to dig deep and find the power to triumph over the weaker among us.

That said, Trumpists - and here I am speaking primarily about those in positions of power - must not be excused for holding such a sophomoric view. Now, I don’t actually know if J.D. Vance or Marco Rubio or Stephen Miller actually has read Nietzsche, and I don’t think that it really matters. David Brooks’s claim is not that they are Nietzsche scholars, but that they are enacting a view of the world that accords with the sophomoric misreading. Their untrammeled desire for power, at the expense of any coherent ideological vision of social policy or cultural theory, is not just dangerous, but intellectually dishonest.

Nonetheless, there are thinkers who do hold actual views like the ones being defended by Trumpists. Those thinkers are people like the Nazi political theorist, Carl Schmitt, who defends the need for dictatorship as the only way that efficient and effective government can occur. For Schmitt, only when the “sovereign” declares a “state of exception” can everything fall in line with the will of one person - incontestable by law. Or, one might turn to the contemporary blogger who holds outsized influence on people like J.D. Vance, Curtis Yarvin (who writes under the name Mencius Moldbug), who explicitly opposes democracy, favoring instead a kind of monarchism that was described in an essay in Commonweal as “too elitist for fascism.” In both of these cases, there is no facade of democratic virtue. There is no pretense. There is just bald-faced power-play.

But the Trumpists present themselves as being the protectors of democracy, of being the one’s who are fighting for the equality of the forgotten and oppressed within our society. This populist garb is, like their Nietzschean flavors, nothing more than a facade. Indeed, I think Nietzsche is actually a profound resource for not only unmasking their shallowness and vice, but also for fighting it on its own terms.

Let me offer just two possible Nietzschean ideas that I think are particularly helpful in this effort.

The Death of God

We definitely don’t have the time to unpack this here, but I have done some videos over on my YouTube channel that might offer a bit more depth if you are interested.

Although a sophomore might read this idea as suggesting that there is now no moral responsibility, Nietzsche sees it precisely the opposite way. When we no longer can rest easy on divine commands, we are left with the heavy task of deciding what will matter. But, unlike Schmitt, we all have to do this for ourselves. In other words, the death of God is the birth of our responsibility. For existentialists like Sartre, it is also the condition of our freedom. Notice, though, that such freedom, such responsibility, requires that we are unable to override the freedom and responsibility of others. This is why Nietzsche hates pity. If everyone is faced with this difficult task of meaning-making, then we should not ever position ourselves such that we take that task away from each and every person. But, that means that Nietzsche is deeply opposed to any authoritarian model of social power.

Simply put, Trump is not a Nietzschean overman.

If he were, then he would be committed to empowering others with their own will to power. As it is, Trumpists are sad, petty, teen-agers who think that power is a zero-sum game of winner take all. Such playground bullying tactics are not Nietzschean. Nietzsche refuses to allow any such external manifestation of power to be anything other than a matter of self-denial lived out in pathetic resentiment. Needing others to be small so you feel big is not to be philosophically enlightened, it is to ignore the lesson of the death of God from the outset.

The idea that everyone should follow you, be loyal to you, never offer criticism to you, and dismiss their own cognitive abilities and their own existential freedom in order to follow your whims is simply the inversion of the very Christianity that Nietzsche opposes. Replacing God with Trump is not a way of completing the death of God, but a way of being an idolater while thumping your chest as God’s chosen. If we really learn the lessons of the death of God, then we will stand up to anything that causes us to bow to external authoritarian pressure.

The Will to Power

The other idea that Nietzsche offers that I think is a real resource for fighting Trumpism is actually the thing that David Brooks seems to attribute to Trumpists as an essential characteristic: The will to power. Yes, Trumpism is about nothing other than power, but it understands power as power-over-others. Nietzsche understands the will to power as a matter of the power of one’s own will to stand up to external authority as necessary for meaning. The “overcoming" of which Nietzsche speaks is not directed at others, but at oneself. Will you overcome your own temptations to abdicate the responsibility and freedom that existentially rest on your own shoulders? Will you refuse to take things from others without interrogating them as likely shaped by the very problematic notion of power to which the will to power is opposed? When Brooks’s says that Trumpists have Nietzsche in their hearts, he does a disservice to Nietzsche who would never stand with Trumpism. Nietzsche famously hated nationalism, he hated the idea that external institutions and organizations could do the work that should be reserved exclusively to one’s own will.

In the end, Trump is not a Nietzschean. Nietzsche does not provide philosophical backing for Trumpism. Instead, Trumpism is unabashedly dismissive of critical thought, of reason-based argumentation, and of hospitality to critique. In this sense, Trumpism is sad and fragile. Nietzsche’s philosophical hammer is something that should be seen as smashing Trumpism into shards of pathetic authoritarian egoism.

I am not interested in sophomoric readings of philosophers. I want philosophy for adults, but that means that we must assume that we are surrounded by adults. Unfortunately, this is an assumption that is simply unsustainable so long as Trumpism has confused the will to power with social domination and the death of God with a Trumpist golden calf.

Ironically, this is one place where Nietzsche and Christians can agree about the death of false gods.

Textual evidence comin' at ya!

From The Gay Science, aphorism 13: “[T]he state in which we hurt others is rarely as agreeable, in an unadulterated way, as that in which we benefit others; it is a sign that we are still lacking power, or it shows a sense of frustration in the face of our own [existential/volitional] poverty . . . It is only for the most irritable and covetous devotees of the feeling of power that it is perhaps more pleasurable to imprint the seal of power on a recalcitrant brow — those for whom the sight of the already subjected (the objects of benevolence) is a burden and a boredom.”

In aphorism 26 of The Anti-Christ (which ends up being more about Nietzsche's opposition to Paul and to what Kierkegaard called "Christendom" than about his opposition to Christ), Nietzsche describes the "administration of justice" and the "tending of the sick and the poor" as requirements "presented by the instinct for life" that are "valuable in themselves."

And despite his earlier criticisms of pity/compassion, Nietzsche writes in aphorism 57 of The Anti-Christ, "When an exceptional human being [e.g., the overman] handles the mediocre [i.e, those who aren't as fortunate, privileged, and/or sophisticated] more gently than he does himself or his equals, this is not mere courtesy of the heart — it is simply his duty."

Long story short: the will to power is the will to life, the will to live, the will to express oneself and to become who one is. (Even flowers turning toward the sun reveal the will to power.) And the need to have power over others? It stems from weakness, from sickness, from the inability to have power over oneself. It's the farthest thing from strength and greatness.

Anyone else a liiiiittle distracted by Aaron’s exposed arms in that fishing* photo?