Setting aside the market realities that usually attend the logic of forewords, namely that having a “big name” write a foreword will likely generate more book sales, forewords are really quite odd. They are literally words before words. Some texts not only have forewords, but “afterwords” as well.

Words before and words after.

Before and after what?

Words.

Words, words, and more words. It can begin to feel like a Dr. Seuss book: “Would you like words on a train? Words on a plane? Words in a frame? Or words down a lane?”

And yet, words are where meaning happens . . . at least for the most part. Martin Heidegger went so far as to suggest that “language is the house of being.” His point is simply that understanding our own existence requires a linguistic frame of reference. It is as if we are ships on the sea and language serves as our horizon.

Words are what provide direction not only for our bodies, “Watch out! You are walking into traffic!” But also what provide direction for our desires, “I love you.” Our plans, “I have decided to major in philosophy.” And our orientations, “I just can’t understand why anyone would vote for him!” In this way, language presses upon us because it allows the world to have weight. We ex-press ourselves in speech when we navigate the world in particular ways.

Nonetheless, words are slippery things. They betray assumptions and historical backgrounds that we have not chosen. Indeed, as Heidegger also says, we don’t speak language, language speaks us. It gives rise to our identities as always already on some course. Just as the idea of disembodied knowledge doesn’t make much sense to the sorts of embodied beings that we are, the notion that we could somehow interpret the world prior to the tools by which interpretations become deployed as live options for us is similarly perplexing.

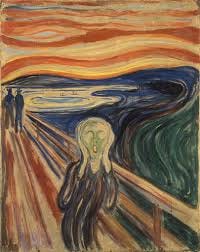

Importantly, though, language is not the same thing as words. Language is the frame of communicative engagement such that the world is a meaning-horizon. Words are tools that we use within that horizon. Notice that a scream and a gesture from a frantic parent might be just as significant as the shout: “Watch out!” A kiss, or an embrace, might convey the meaning that the words “I love you” are meant to express. A silent political rally with bodies linked arm and arm might enact political confusion as well as any op-ed might. And so on. So long as meaning continues, language seems to be necessary, but words (as signs in a “natural” language) may not be.

Somewhere in his expansive authorship, Jacques Derrida suggests that we must “make the limits of our language tremble.” Derrida’s entire deconstructive philosophical methodology is precisely to engage in such a task. His work is an invitation to pay attention to what we normally ignore. Words are not only used to convey meaning, but they also often (always?) fail to say enough because they are always (often?) saying something that we didn’t intend.

Again, language speaks us. We are pawns in the speaking of language in which we engage. Words open worlds, but they also prevent us from transcending the world in which we find ourselves. Derrida is often said to “play” with language, but he, perhaps more than any other recent thinker, has helped us see how language is really the master of the game. Playing around with words is very serious business.

J.L. Austin attempts to teach us “how to do things with words,” but the mastery that such speech-act theory requires is something that Heidegger and Derrida both interrogate . . . with words. Do the limits of language occur linguistically? Can they be spoken about? Ludwig Wittgenstein suggests that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” but are such limits themselves expressible? If so, wouldn’t they be within the limits? If not, then how would we be able to make sense of the limits, as ‘limits’?

Words world.

World words.

World worlds words.

World without words?

Words against words.

Words against world?

What?!

If language is the horizon of meaning, and the limits of language are the limits of the world, then is it even possible to confront meaninglessness? It seems that words can sometimes express by failing to mean anything at all. Consider Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky.” “Twas brillig, and the slithy toves”—is this saying anything? Or saying too much? How would we be able to tell the difference?

I recently had three students who lost parents very tragically and unexpectedly. In each case, I emailed them and “said” that I was “without words.” And yet, I used words to say I didn’t have words. Were those words marking the limit of language? Were they actually the “right words” for the occasion?

Sticks and stones can break my bones, but words can never hurt me.

This is false.

Proverbs rightly claims that the power of life and death reside in the tongue. Our words open the spaces into which we then live. Our words close down the lives of those who don’t fit into our spaces.

Regarding linguistic spaces as existential opportunities, mystical theology understood the complexity of language long before the hermeneutic phenomenological approaches of Heidegger and Derrida. The apophatic approach to theology was defined by a recognition of the failure of words to be “adequate” to God. And yet, such inadequation, itself, happens in linguistic contexts. Saying false things about God, in the apophatic tradition, was not something to avoid, but was unavoidable. The goal was to discover truth in the enactment of the falsity. As we learn that our words fail to say anything about God, we also open ourselves to God as beyond our own conceptions. The rest, for the mystics, as for Hamlet, is silence.

Silence doesn’t say anything and yet it speaks volumes.

Interestingly, silence has a two-fold ontology. It can result when one doesn’t have anything to say. It can also result when regardless of what one says, one can’t ever say enough. We might term the former the silence of lack and the latter the silence of plentitude.

When I tell my students that I am “without words,” I am expressing the silence of lack. When one is brought to one’s knees due to the sublimity of a mountain range, say, or when looking up at the Sistine Chapel ceiling, for example, we face the silence of plentitude.

In the tension between these two silences, human existence happens. As a sustained reflection on what such existence means and requires of us, philosophy is, thus, a liminal discourse—but a discourse, nonetheless. In contrast to science, which is always an attempt better to speak of what is the case, philosophy runs up against the possibility that what is the case might not be available to speech . . . at least not completely . . . the best we can tell . . . from where we stand . . . using the linguistic tools we have at our disposal.

In this way, philosophy is fundamentally about questions marks, rather than periods. Yet, it not only questions our beliefs and views of the world, but puts us into question.

· What is true?

· What is beautiful?

· What is good?

These three questions are the core of philosophy because how we answer them forms the core of our identity. Our lives are designated by where we put periods to the questions we confront. In this sense, Pierre Hadot is right to view philosophy as a “way of life,” rather than simply as a professional activity of a particular academic discipline. It is a way of approaching life as a matter of re-orienting ourselves as comfortable with questions and setting sail toward Truth as the horizon worth pursuing.

Problematically, though also, as we are beginning to see, quite predictably, if philosophy is such a way of life, how then do we teach it to others?

Unfortunately, most philosophy is taught simply as a history lesson: here is what other philosophers have said as answers to the questions that define the human condition. Yet, philosophy is not a matter of the answers offered, but an existential invitation to being put in question. Here words begin to fall flat (notice though that I am still using a metaphor – of spatiality and the different senses of ‘flat’ – here to try to say something that isn’t simply a matter of linguistic articulation).

What are the right words to use to invite others into the “way” (the Dao?) of philosophy?

I think philosophy should invite us to become active, embodied participants in existence by running us up against the limits of language. Simultaneously, though, it also should encourage us to see the world as not fully formed and presented to us, but rather as inchoately emerging as a possibility requiring our action.

Nietzsche reminds us that there are questions and question marks everywhere, but he also requires us to wrestle with the fact that we have not yet lived into the ramifications of the death of God so long as we believe in grammar!

When God dies, we lose our horizon. If language is the horizon of meaning, then the death of God is the condition of becoming unmoored.

Without direction, or free to chart our own course?

Language is the house of being, but maybe this house is a prison.

When philosophy becomes a way of life that draws us into the wild spaces of meaning and existence, we are not presented questions in order for us to show that we know the right answer, but so that we can humbly admit that we may too quickly cling to the answers that allow us to ignore the questions in the first place. Through some very serious play, philosophy offers a space in which we all are given the opportunity to become gods ourselves—or maybe, finally, to become human.

We are meaning-makers when we are question-askers. We are philosophers when we see the questions as not only worth asking, but living.

But the question(mark) will always remain: perhaps philosophy will leave we readers, we interlocutors, we demigods, with nothing but the silence of lack.

?

Perhaps philosophy will walk with its readers, its all too human friends, into a world in which silence never says enough but enables us, ultimately, though always contingently, to speak.

?

Perhaps?

Perhaps.

Philosophers often say far too much about far too little. Nonetheless, it matters that we continue to speak . . . whether or not we use words.

There is always a meaning-horizon one way or another. The real task is, as Tennyson’s Ulysses charges: “to sail beyond” it.

The wise among us use strikingly few words, and yet say more than might initially be realized. They opens the space for others to speak, to think, and to become.

Beyond words, life continues. In words, life continues. Without words, life continues.

With that said, then, life awaits. Interesting. Maybe “forewords” are not just words before words, but rather signals for the importance of lived speech. Forewords motivate our attention forwards . . . forwards into the significance that happens in our speaking forewords.

Our lives are texts. And as Derrida also “says”: There is no outside of the text. Thank God.

Here we run up against what all apophatic theologians understood: When we reach the name of “God,” perhaps we have said enough.

What else, indeed, would be left to say?

Having a “big name” author a foreword is in part an addition to the marketing process. The potential reader thumbs through the foreword, thinking that the well-known, perhaps erudite, writer of that first taste of the text is saying, “look now, I’m smart, an expert in this area, and that tells you all you need to know about why you should buy and read this book.”

In your post I’m drawn to the hints that connect us to what we read and what entices us toward further inquiry. I’m interested not only in what I glean from a text, but what new curiosity it may open in my mind. The image of a young Lawrence Olivier stumbling on the skull of “poor Yorick” and triggering memories of youthful pleasure, at a time in Hamlet’s life when he carries a terrible burden. And all the rumination he summons to carry as he thinks of the task ahead of him. A lot of silence there, and the photo of Hamlet holding the skull affectionately to his cheek gives him a brief respite from what he can’t escape. He puts down the skull and moves toward his destiny.

Our plans, “I have decided to major in philosophy.”

Some poorly-veiled self-promotion/departmental propaganda! lol

This makes me think about Kant's religion and pure reason arguments, although I cannot recall the specifics (it was 30 yrs ago).